With each Mentatrix, we take a look at the world outside, and learn more about the world inside.

I’m bringing you a Mentatrix that has been on my radar for over half a year. It’s taken this long to brace myself and dive into the story. Stay with me, please.

We’re looking today at a policy in post-war Germany, both East and West, that prescribed recreation and health-improvement stays in health centres for kids who were considered underweight, behind in the growth process, or suffering from lung ailments such as bronchitis. Children would spend six to twelve weeks in such centres at the North Sea, or in the mountains (including in the Black Forest), and were to be fed properly and overall re-educated in the spirit of sound hygiene.

Ironically, these re-education and nurturing centres turned out to create traumatic experiences through a sometimes inhumane treatment of the children, ranging from humiliation to physical abuse.

This is the story of the dispatched children (Verschickungskinder), and what it tells us about ourselves.

Who were the dispatched children, and why were they sent away?

Two to ten year olds would be sent away from the family on health and recreation stays prescribed by the family doctor, by the Public Health authorities, or sometimes by the Youth Welfare Office. Symptoms such as underweight, constitutional frailty, or paleness could be enough for kids to be sent off. Weight gain was the main metric to testify the improvements.

Interestingly — inexplicably, from our modern point of view? — families had no say in these decisions. It was a matter of state policy.

As TB, as well as other diseases, became less frequent, the sanatoriums were facing the threat of becoming obsolete. That is, apparently, a reason why doctors were getting incentives for prescribing a spa treatment. The beds in the health centres were now filled by kids, sometimes reasonably healthy, who allegedly required a recreation and health improvement treatment.

What were these institutions? Who was the staff?

Health centres, or sanatoriums, first appeared mid-19th century in Germany and Switzerland, in particular to treat TB or provide rehabilitation after respiratory disease. A change of air and diet, hygiene instruction and a daily rest routine made up the offer of such sanatoriums.

In the aftermath of World War II, when the population was faced with large scale poverty, undernourishment and overall precarious living standards, such health centres were increasingly used to improve children’s health. Between 1947 and mid-90s, an estimated fifteen million children were prescribed a recreation and health-improvement treatment in a remote sanatorium.

The personnel included mostly nurses and caretakers with a minimum qualification. A medical doctor’s supervision was often limited to occasional visits of a spa physician. Some of the sanatoriums belonged to the Church, so the personnel was simply — nuns.

Although the main age group targeted were pre-school kids, there was no staff with pedagogical or psychological training. There were no toys, playing rooms, or other age-suitable didactic materials.

It’s worth taking a moment to realise who these caretakers and physicians were: the generation that grew up and was integrated in the society under the Nazi regime of the 1920-30s. They were not only nurses or caretakers that had witnessed or assisted in surgeries such as sterilisation or euthanasia, aligned with the Nazi ideology; some of them had held key positions, issuing expert appraisals or coordinating often deadly experiments on children or “undesirable” categories of people, for clinical research related to drugs, sedatives, or vaccines.

A prominent example is the head of the sanatorium for lung disease in Hohenlychen (Brandenburg), Karl Gebhard — Hitler’s personal physician and former head of the concentration camp in Auschwitz1.

This generation started leaving the stage in the 70s, but it was fully gone in retirement by the end of the 80s.

What went on in the sanatoriums?

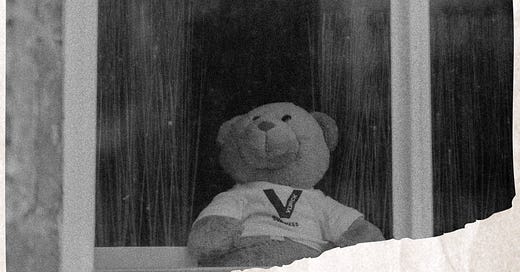

Children were sent away without the parents, and kept in isolation from their families: no visits and often no post were allowed; alternatively, the post was censored to ensure only sunny impressions of the recreation were sent back home.

Not all kids suffered abuse.

But practices such as forced eating or bans of toilet use are mentioned in hundreds of self-reports that are being gathered starting from 20192. Extreme punishments and humiliation if the terrified child threw up, burst into tears or peed in the bed included forcing the kid to eat the vomit while the others had to watch, being tied to the bed, sedated, isolation over weeks and months, or having to stand still for hours.

Symptoms were sometimes developed such as obsessive wiggling, nibbling, scratching the walls, crumbling bread or smearing faeces. Many other traumas, persisting through adult life.

The food was torture. Because I was too thin and weak, I alternated between rice pudding and semolina porridge every day. The cod liver oil I was given every day in the morning and evening regularly made me throw up and I had to clean it up myself afterwards. I often sat at the table for an hour or two until I had choked down the rice pudding while all the other children were outside. Even today, I get a gag reflex just thinking about rice pudding.

I still remember the constant thirst, as there was nothing to drink from the afternoon onwards, the thirst was so great that I sucked the flannels of my bed neighbours out of desperation, they were left on the edge of the bed to dry. In the mornings there was always a red pill from a large silver tin and anyone who wet their bed had to go to the cellar and get a shot in the back, anyone who looked at the doctor, which was forbidden, got a good slap in the face.

The worst thing was that we were only allowed to go to the toilet three times a day, after each meal. Outside of these times, the toilets were locked, even at night. It also happened once that toilet time was cancelled for the whole group because two children had laughed loudly during lunch. Everyone can imagine how it stank in the room after a nap. The constant wetting and defecating traumatised me for many years. The punishments and slaps were the lesser evil, the shame and embarrassment were worse, although I wasn't the only one. Many children wet their pants or the bed. After the "cure", I was a nervous wreck and wet the bed for at least six months.

Even today, I still find it difficult to write about Furtwangen. I was sent to this hell for 6 weeks back then, although I fought it tooth and nail. What I experienced back then is still present and a nightmare. Children were tearing their hair out with homesickness. The weekly examination, for which you had to line up naked in a dark, cold corridor without separating the sexes, was the worst thing I had ever experienced. I don't think any of those responsible are still alive. Let them burn in hell!

Children who vomited on their plate had to stay seated until they had finished eating. Followed by two hours lunch break. We were not allowed to get up to go to the toilet. A carer sat in the stairwell and kept an eye on us. We crawled to the toilet on our stomachs and hoped we wouldn't get caught. My neighbour sat on the edge of the bed and rocked on it to suppress the urge. For me, not being allowed to go to the toilet was traumatic. I was always afraid later that I wouldn't be allowed to go if I had to.

What does this story tell us?

So many things!

The dangers of an over-protective state, to the extent that it intervenes in its citizens’ private lives.

The horrors hiding in going all in, pushing it the whole way, aiming for the 100%. Fanaticism. The message of good intentions paving the way to hell. No. Creating a hell. The hell of rules and utopias. Another facet of the New Citizen we, in communist Romania, were pushed to emulate, to become.

Another piece of evidence that horrors don’t only happen because of, or in the course of a war. Peace time and normal life are equally prone to cruelty, torture, or even crime against humanity.

The risks of taking the shortcut and relying on rules, policies, going by the letter, instead of the spirit. Ticking boxes instead of dealing with the individual case. Asking yourself each time, what am I doing, and is this serving what I am trying to achieve?

Is limiting toilet use really going to get children to get a sound sleep? Is eating up the way to gain weight and is weight gain the ultimate goal?

The terrible temptation to crush what is soft and fragile and squishy — especially living beings.

I remember a time in kindergarten when I had a short-lived crush on another girl. She was pale and a bit plump, and had a thin voice. Large watery eyes. I felt the urge of nudging and pinching her, squeezing or twisting her arm or fingers. Getting her to say ouch and seeing her face crumple up with pain. Like sticking my finger in jelly and watching it wobble. I remember the build-up in me, wanting more and more of it, pressing harder, squashing and pushing further. My lips pursed and my jaws tightened. A sort of hell, I’ll get you now!

It was a passing phase, thankfully. Kids’ world.

But it’s in us. The fascination with someone else’s pain, if it’s us who inflict it. Watching. Grinning.

If punishments were not in place, how far would we go nudging and pinching?

Crushing and maiming?

Until he was sentenced to death in the Nürnberger trials, in 1947.

Since 2019, former Verschickungskinder have started going public about their experiences in the children sanatoriums. Following the founding of the "Initiative Verschickungskinder" and the association "Aufarbeitung und Erforschung von Kinder-Verschickungen", work began at state level in 2020. A resolution passed by the Youth and Family Ministers of the federal states in May 2020 stipulates that research is now to be conducted at federal level. Verschickungsheime

It reminds me vividly of my own daycare/kindergarden

Suffice to say that when I went to first meeting for parents, my own toddler preschool, different country-different times, I started crying, real tears, because I realized it'd be different, she'd be loved, or at least not hurt.

It’s hard to like this because it’s so disturbing, but you taught me a lot.