One hiking tour in southern Black Forest promises to take you through wild ravines up to Balzer Herrgott, a Christ head in the trunk of a tree. A hike that’s nearly 16 kilometres long, covering an altitude difference of over 600 metres, is not a trifle; but seeing the natural miracle with your own eyes is definitely worth it.

I mean, a hike through wild ravines and over steep mountain sides is definitely worthwhile without any other miracles.

I have seen pictures in the hiking app, but I don’t care to read about the miracle ahead of the hike. I prefer the live experience. It must be that mixture of nature’s random shapes and the human eye seeking familiar patterns, like an angel in the clouds or an animal in the contour of a cliff.

The less obvious, but even stronger attraction is that Balzer Herrgott is no tourist point. You can only get there on foot — by sweating through the climb. Once there, no inn, not even the rustic hut typical in the Black Forest, which is open at weekends in summertime and sells the usual beer, apple soda and home baked apple cake.

It’s you, that tree and its Christ, and the wooded mountains cutting out the skyline into a wavy frame.

It’s a sunny October day when, around lunchtime, with the sun at the zenith, I get to the meadow on the peak and see the spot a short distance ahead. A thick tree in the middle of a round place, which is gently but unmistakably marked by boulders placed there as if to create a shrine.

Several hikers are having a rest a few feet away.

The path approaches the place from a side, so that you can only see the Christ when you’re there.

I stop near one of the boulders, and contemplate the wonder. I now know it’s man made, somehow.

And yet, not much is known for sure about how a Christ head, part of a larger statue, got to be stuck in a tree trunk. One story goes that it was abandoned by Huguenots fleeing from France. In another version, the fugitives were French royalists during the French Revolution. A local farmer says that it belonged to a monastery, but was hidden in the forest to protect it from damage during the war.

Most likely, apparently, the Balzer Herrgott was part of the cross in a farm chapel nearby. This farm was destroyed by an avalanche in February 1844 (although some versions place it in 1700), and the arms and legs of the Christ figure must have been broken off. It must have been lying on the ground in the woods for long decades until it was attached to the tree by two clockmaker apprentices around the turn of the twentieth century.1

But how did it end up inside the trunk? How was it possible that the tree overgrew it?

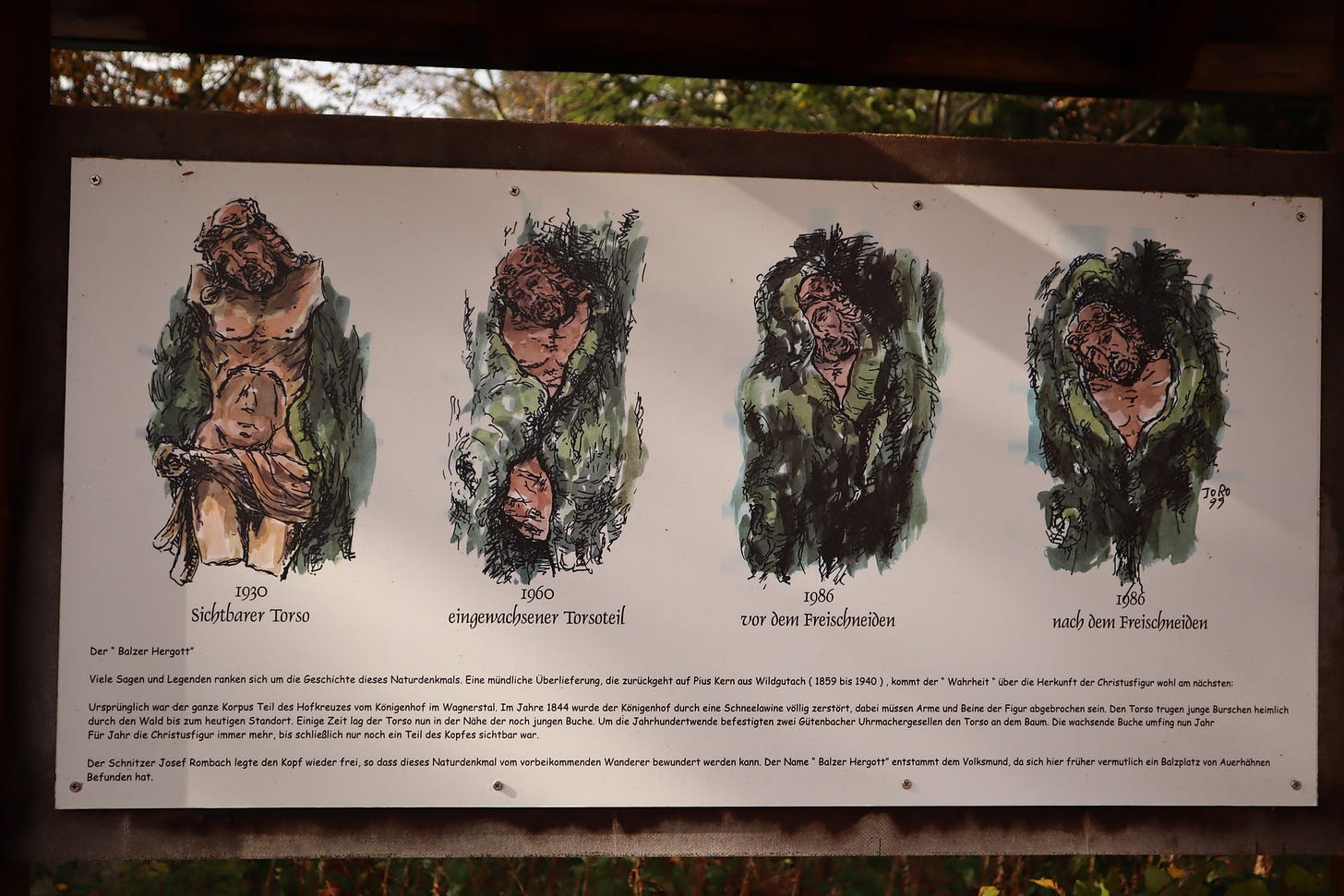

An info board shows the stages.

This is a pasture beech, which develops when the shoots of young beeches are repeatedly eaten away by grazing animals, such as cows and goats, or by deer. The trees grow new shoots again and again, until they form a bush. When the bush has got so thick that the animals can no longer eat the shoots at the centre, those young trees grow together.

In around a hundred years, the trunks begin to blend together and form a single mighty tree. The tree of the Balzer Herrgott is made up of about ten original stems, which can still be discerned.2

It soon becomes clear that the Christ would have been swallowed by the tree by now, had it not been carved out of the trunk in the 1980s.

That’s where the human element gets back into the story.

In November 1986, a local carver uncovered the head and chest for the first time. Tree specialists sealed the exposed wood against fungi and moisture and created an artificial bark. In 1995, the growth of the tree had to be stopped again, as it threatened to break the head.

Here’s a translated account of the expert protection measures:

Rain water running down the trunk of the beech into the area behind the head of the figure caused further damage. Further restoration was undertaken, in consultation with the district's monument protection authority and the local forestry office, which was completed in 2014. A tree expert cleared again the area around the head, and removed any neighbouring branches. A picket fence was put up to prevent visitors from unintentionally causing damage by touching the sculpture or attaching personal items. The root area was marked and demarcated in a circle with boulders so that heavy forestry equipment could not cause any damage to the roots. The area between the beech tree and the circle of boulders was also covered with mulch to minimise the impact caused by groups of visitors. An inconspicuous small sheet metal roof in the shape of an angle was attached to the tree trunk above the figure of the Christ to drain off rainwater. A natural tree fungus was also attached directly above the head of Christ for this purpose. A local stonemason has also expertly prepared the remaining figure in such a way that further damage caused by running (and freezing) rainwater is avoided as far as possible. Balzer Herrgott – Wikipedia

Did I think it was a natural wonder when I left home that day?

Or is it, almost disappointingly, human made? Was it at first some human fatality, negligence, oblivion, followed by a cult of maintenance nowadays?

Or is it both, as so often in this Black Forest landscape I love so dearly: nature and human settlements blending into a harmonious and often breathtaking picture that blurs the boundaries between one and the other?

Just like this Christ head carved out of sandstone, blending in the bark of a centuries old beech tree, yielding a “wonder”.

What lured me to that place was the mystery, the miracle. It stirred my curiosity and took me several kilometres out there, the pilgrims’ way, over alpine pastures, down rifts, along bushy canyons, up a steep hillside again, to see. To contemplate what nature, man, and some godly entity may have worked together to create.

Here was a mystery — and how fond our minds are of mysteries! For all the modern-day addiction to data, we sense at times that knowledge is overrated.

(Although this is strangely exploited in political campaigns, instead of cultivated as acceptance of a universe that infinitely exceeds the powers of our imagination.)

In the face of a spellbinding story, truth becomes irrelevant.

Further on, mystery engenders mystery. Around a miracle emerges a story. And another story. Several stories — very often, none of which can be pinned down to historical evidence. To data. To knowledge. The tales are enjoyable in themselves, with or without historical proof, by feeding our minds more mystery. It’s the flavour of remote ages and their adversities; or the mesh of hearsay and oral testimonies, never captured black on white into prosaic evidence, but blending fates of the told with those of the tellers into an all-engulfing mystery of the old.

Very much like the Christ being swallowed by the tree trunk.

Contemplating the tree, you also see right there before your eyes the process of nature overgrowing whatever humans have, or will ever create. That irreversible dissolution of our bodies and yearnings into the grand universe beyond us. Beyond, and still, within us, wrapping us in, holding us, absorbing us into our graves.

While we’re still here, though, Balzer Herrgott tells about our need to hoard and preserve. We don’t just love a mystery; we care for it. Yes, care. This is a world of destruction, and still, we care about our relics, about the vestiges of our stories. The professional investment in this beech’s miracle cannot be overlooked. It touches me with its minute attention to detail. It touches me that some picket fence does hold the protection, where only a bit of kicking could put it down and give feet the freedom to trample around.

The composure and respect our hearts are capable of paying. Not for some material gain, but for the love of a mystery.

As described here: Baumwunder Balzer-Herrgott

I completely agree with what Jill stated, and also found fascinating that "The tree of the Balzer Herrgott is made up of about ten original stems, which can still be discerned."2

And, I also appreciate your sentiment, "The composure and respect our hearts are capable of paying. Not for some material gain"...

You combined fun, adventure, contemplation and interesting history- I enjoyed reading this essay!

Beautifully written and can be understood on many levels. Two lines in particular struck me:

"In around a hundred years, the trunks begin to blend together and form a single mighty tree."

"nature and human settlements blending into a harmonious and often breathtaking picture that blurs the boundaries between one and the other."

The first quote makes me also think about people, and generations and the stories that we tell that bind us. Can we become blended together, single and mighty, across generations?

The second quote is an aspiration that you beautifully articulated.

Loved it all!