Hello, Mentatrix readers! This post may be too large for your inbox, because there are lots of pictures, so you might need to read it in the app or browser.

Today I’m back to the Mindful Wanderer series: nature and reflection. My Black Forest hiking app tells me I’ve completed about 75 trails. There are hundreds more awaiting me. A lifetime to enjoy them all.

Having walked so many paths, I can step back and get a broader picture. The Black Forest is like us: it goes through stages, projects, versions of identity. Follow me!

In the beginning, the Black Forest was a huge, thick forest: Silva Nigra in the language of the Roman armies. There must have been but scattered, isolated tiny settlements of a primitive Germanic population, huddled together in a clearing, sheltered by surrounding bushes, close to a water source. The place was a given, humans had to take it or leave it – go survive somewhere else.

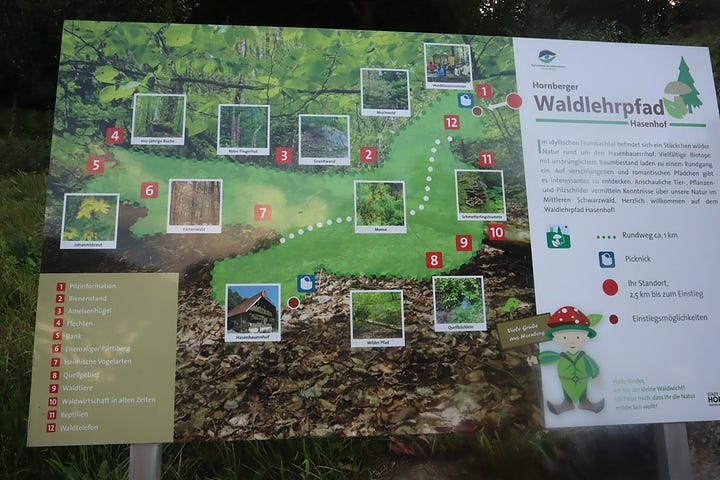

The Black Forest is both nature and about-nature. Both wilderness and info boards that document it. Preservation as both authenticity and showcasing, even outside the boundaries of the national park per se. Almost a mirror of mindfulness, which is both being and the awareness of being.

One of the things that strikes the hiker is the diversity of the landscape. Dark forests, light woods, meadows, pastures, vines, orchards, moors, gorges, waterfalls, lakes. The horizon is jagged, bulky, wavy, flat, spiked by trees, or animated like a gif by water surfaces.

A deeper diversity lies not in the views lined up along your path, but in the successive transformations over centuries. Interestingly, the traces of these past landscapes coexist nowadays; sometimes an info board illustrates what that particular place used to look like a few centuries ago, and then the eye becomes aware of how the past blends into the present version of the place.

Add to this old Black Forest stories about its people and their lives and livelihoods, and it strikes you how the landscape transformation has reflected the changes in the people’s values, beyond mere survival.

After the Roman armies came the monks and missionaries in a “civilisational” action. Trees had to be felled to make room for a monastery, later a fort, and around them a settlement.

Felling more trees was necessary when the promise of economic prosperity emerged, not just for the landowners, but for entire villages. Wood, ore, and later the related crafts meant that large areas of the Black Forest were reshaped to fulfil a function. I wrote elsewhere about the Black Forest being one of the main sources of wood that the city of Amsterdam was built on (read here the full story). The wood owners made fortunes selling their fir trees: depending on its size, one such tree could fetch a teacher’s salary for an entire year.

Sometime in the nineteenth century, however, industrialisation kicked in, and with the scale that it enforced, a new vision emerged; the landscape started changing again.

Some landowners began to realise that cutting down trees was not sustainable. At a certain point, there would be no more trees to sell. So they started replanting trees and keeping records of which surfaces can be felled, and when. More or less at the same time, many old mines were abandoned because they were no longer economical. The entrances to such shafts are barely visible nowadays.

Instead of the once thickly wooded areas, there were large surfaces for crops or pastures. But that meant more exposure to bad weather or a higher risk of landslides. There had to be some balance between vines, pastures, orchards, and woods.

A new asset was discovered: spa tourism, and with it, the value placed on less tangible (or exploitable) resources: the air, the altitude, the quality of the water, the virgin landscape, the sense of being “far from the madding crowd”. This was, however, reserved for the well-off, as a pleasure that life offered to those privileged enough not to worry about subsistence.

After the wars, the new wave of prosperity meant the creation of an infrastructure that made the locals proud: railways, roads, and large factories turning Black Forest's traditional crafts, such as clock-making, into a global business. Again, the landscape changed to accommodate people’s values.

But soon, the environmental concerns gained hold. With them, the cultural awareness: what do we need to preserve, maintain, and take care of, so that the Black Forest retains its identity? Our identity.

The infrastructure was limited not just by profitability (as in, is it worth cutting through ten mountains for a full-scale railway?), but also by a drive to keep the landscape natural, rural, and ancient. There is no motorway crossing the Black Forest. From the western side, where I live, facing the Rhine, it takes an hour and a half to drive across to the eastern side, on the Swabian high plains: just about a hundred kilometres.

This trend has kept growing in the past decades. Woods are closely monitored, refreshed where necessary by new trees, or left to develop on their own, for humans to watch, over generations, how nature changes if left by itself. The concept of the so-called Bannwald, ban (protected) forest, emerged; the area is protected by not taking any action to shape it, not even to trim and tidy up in the wake of a storm.

A certain culture of the gaze, of contemplation was born. The landscape that used to be shaped by the people’s economic needs is now partly left on its own, or helped to regenerate as virgin wilderness so that people can retrace their ancestral connection to the environment, or simply contemplate a particular kind of “beauty”. Such contemplation spots are lovingly created by mimicking primitivism, and a rustic flair, such as log benches, kiosks, animals or bizarre human figures carved out of wood, even a “forest shower” that looks like a Robinson Crusoe gadget.

This is no longer elitist spa tourism. It’s for the hiker of the village nearby just as much as for the traveller from hundreds of kilometres away, who came for an outdoor experience. The contemplation spots are created by local people, small companies, or the local outdoor Black Forest association (Schwarzwaldverein).

What will the Black Forest of the 2080s look like, I wonder? Will the revival of the far right politics leave any traces, and how enduring will they be?

Looking back, it seems to me this place mirrors the individual journey from simply being to chasing external goals and ambitions of growth, to finally both being and awareness thereof. While no single past stage defines us, all past stages are part of who we are in the present.

All the past versions of this region are visible to a mindful hiker: from thick forests like those that preceded the name Silva Nigra, to the blend of human-made landscape nowadays, with its abandoned economic projects or revived passions, and to the wilful identification with the Black Forest construct.

It would be interesting for each of us to look around and spot that element of human values and purpose that drives the change of the landscape where we live. Is it a drive for more comfort and convenience? A drive to get more money and richness? A drive for embellishment, for a back-to-the-roots aspiration? One for the landscape as a mirror of our identity – or as a mirror of ourselves as spiritual, mindful beings?

And then, direct the same gaze from the surrounding views inwardly. What stage are we in, as an individual? Are we “just” being, no further thought spent on it? Are we driven by goals and achievement ladders? Are we trying to entwine awareness with being? Or are we maybe getting lost in contemplation?

What past versions of ourselves could someone else spot in us? What past versions of ourselves are we trying to hide? Or what versions have we discarded completely and are just relics in the archive of our becoming?

Until next Sunday!

Very interesting. Two particularly excellent lines that grabbed me:

How the landscape transformation has reflected the changes in the people’s values, beyond mere survival.

Looking back, it seems to me this place mirrors the individual journey from simply being to chasing external goals and ambitions of growth, to finally both being and awareness thereof...

I was unfamiliar with the term "spa tourism," but as soon as you wrote it, I understood it.

Well done!

Thank you for your beautiful post Zoe. I've been planning a visit to the Black Forest since last year. Can you tell me the best time of year?